As the world works towards its common goal of decarbonization, the carbon footprint of datacenters has increasingly been in the spotlight. This is mainly due to the fact that AI and the vast digitization of our societies require enormous amounts of energy at a time when it is still difficult to deploy clean sources that work around the clock.

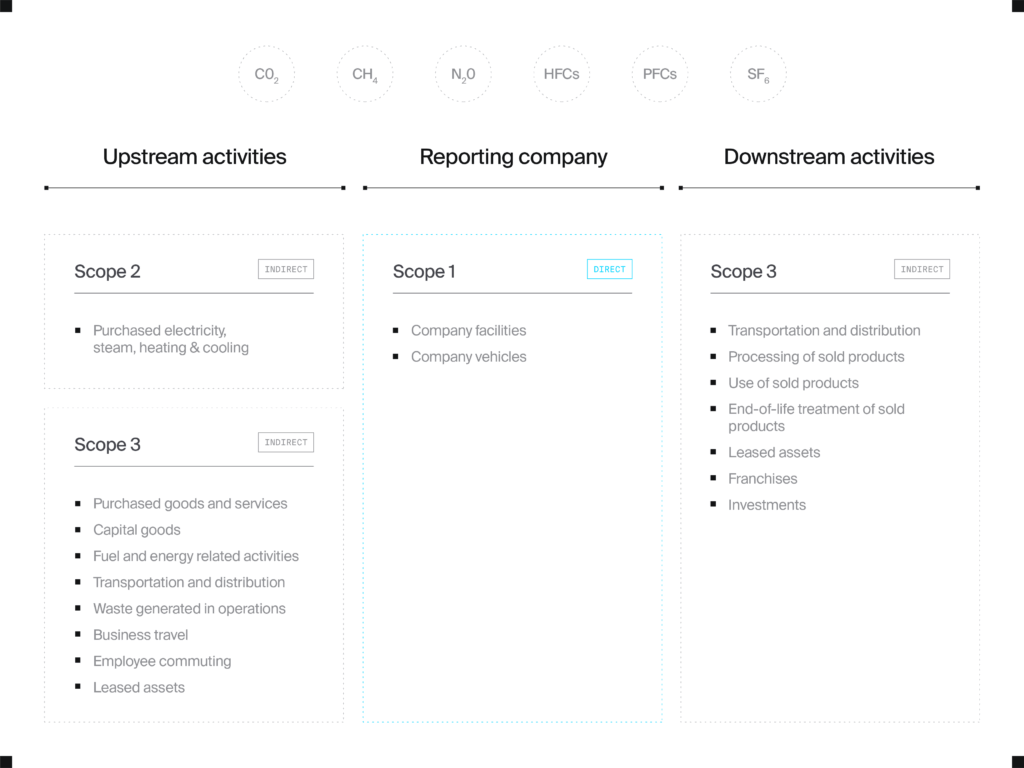

Estimates of datacenter’s carbon footprints have matured along with improved reporting across industries. Large, public organizations are the most inclined to be reporting their Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions in alignment with the globally recognized GHG Protocol, and the datacenter sector is no exception. A gap still exists for smaller and private organizations, specifically for Scope 3, notoriously the toughest category to measure and tackle. This is important as the vast majority of emissions for datacenters can be attributed to Scopes 2 & 3. The proportion attributed to each scope will mainly depend on the operator’s consumption from clean energy sources, which, when deployed effectively, helps to reduce Scope 2 emissions. In terms of types of GHG emissions, the largest proportion comes from CO2. Methane (CH4) can be linked to Scope 3 if coal or other fossil fuels are used for power generation. Moreover, another small percentage can be attributed to refrigerant leaks from HVAC systems, which have large Global Warming Potentials.

The results so far – Greenhouse gas emissions on the rise

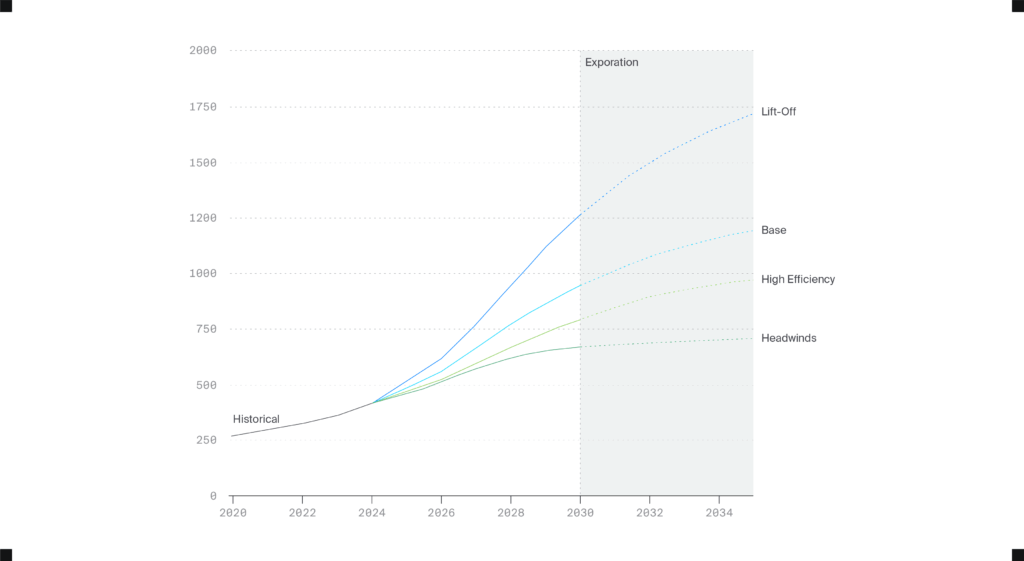

As we have seen previously, datacenter electricity consumption is projected to continue its upward trend. The IEA recently released a new report on the impact of AI on electricity consumption of datacenters. They highlight that it has grown by around 12% per year since 2017, at more than four times the rate of total electricity consumption. Furthermore, this growth is projected to continue.

The report also stresses that this issue is regional. When compared to other industries in the process of electrification, such as automation, datacenter electricity needs are projected to represent less than 10% of the total. However, due to concentrations of deployments in regional hubs, certain regions are projected to see the largest growth. This could cause strains on grids and higher GHG emissions as carbon-intensive energy sources are forced to remain and are deployed further.

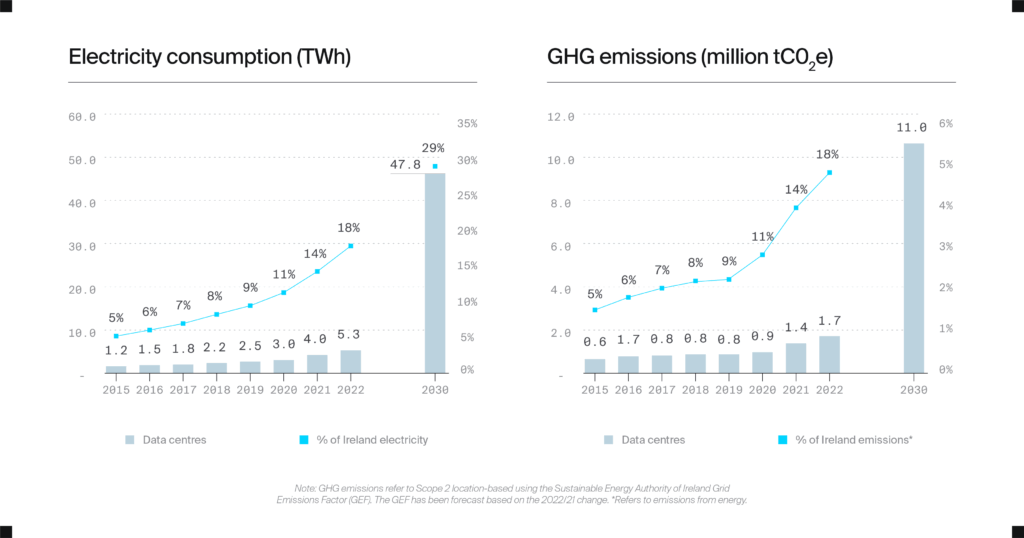

To give one example, we can find that Ireland’s datacenter electricity requirements could multiply from 18% in 2022 to 29% of total electricity needs by 20301. This would entail a more than six-fold increase in GHG emissions for the sector in that eight-year timeframe, right at a time emissions in developed nations should be going in the complete opposite direction.

Source: Measuring the Emissions & Energy Footprint of the ICT Sector, A Joint ITU/WB Report

Ireland and other workload-dense locations rightfully see datacenters as an enormous source of economic prosperity, but this is clashing harshly with the need to decarbonize in line with the Paris Agreement.

Moving forward, more granular data from individual datacenters is required in order to improve precision and verify projections.

Certain GHG emissions are still hard to measure

Most electricity passes through the grid as it is the most effective way to balance the varying needs of supply and demand. This complex system with many actors makes it impossible to know the exact energy source of each kWh consumed.

There are two types of Scope 2 reporting in the current version of the GHG Protocol. Location-based reporting makes its calculations using the local grid of each datacenter. However, this fails to quantify for any Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) that the datacenter might have negotiated with local utilities using clean energy. In this methodology, the datacenter would not be able to benefit from the reduced emissions linked to this electricity generation and consumption.

In our previous piece, we also mentioned a quirk with the other Scope 2 methodology, market-based. This type of reporting allows corporates to claim they use 100% renewable energy, when in reality they are still consuming fossil fuel generated electricity and then purchasing unbundled Energy Attribute Certificates (EACs) that represent clean sources of energy. This clean energy does not even need to be generated near the location of the datacenter consumption. In practice, a datacenter in Virginia consumes 10MWh from the PJM grid, with a fossil fuel-generated energy mix of over 50%. Then, two months later, they can purchase a Renewable Energy Certificate (REC), a type of EAC from a wind farm in Texas for the same amount of MWh. By doing this, despite the mismatch in location and timing between the energy generated and consumed, the datacenter company in question can feasibly consider itself 100% renewable based on current market-based Scope 2 accounting. Unbundled EACs continue to help wider-decarbonization from a holistic approach, but current reporting is helping datacenter organizations to put off the hard work of true decarbonization out into the future.

Another hurdle is related to who is responsible for the emissions. In a notoriously complex industry, colocators generally pass on electricity bills to their clients and have little visibility nor interest in knowing how efficiently the workloads are being run. This entails that customers must report related emissions under Scope 2 and the colocator must do so under Scope 3. Colocators at the forefront such as Akamai have highlighted the inconsistencies in reporting and the need collaborate in order to improve reporting.

This is not the last of the worries for datacenters as there are many more categories in Scope 3 emissions that are notorious for being the hard to measure. As this is a large topic in itself, we will cover it in depth in a future blog post.

Improving datacenter GHG reporting

Government regulation is necessary in levelling the playing field. Slow progress for reporting under the EU’s Energy Efficiency Directive (EED)2 shows that datacenters must take a more proactive role in providing valuable information that will help the industry to improve its impact. This includes the reporting of the energy consumption of servers and storage, long considered a gaping hole in the industry as operators refuse to disclose this data publicly.

The EED is currently being revised further with ambitious targets for datacenters. Submer is a big advocate of this piece of legislation as it likely to be impactful in improving energy efficiency. If implemented correctly, it will set a new standard for transparency that will enable operators to benchmark performance, identify inefficiencies, and track progress across facilities in a comparable and standardized way.

Today’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions reporting continues to mostly be a retrospective affair. Globally, more granularity is needed to be able to analyze performance and make adjustments on an ongoing basis. Beyond regulation, datacenters must strengthen their GHG reporting by embedding strengthened governance structures at every level of the organization. Rather than treating emissions reporting as a reactive response to regulation, ongoing monitoring enables proactive oversight of risks and opportunities, aligning climate goals with the company’s strategic direction. This includes emissions tracking at a granular level internally and in the supply chain.

Our next piece will focus on the largest challenge, moving from measurement to action. How will datacenters fully decarbonize in line with the Paris Agreement?

- The Future of Data Centres in Ireland, Houses of the Oireachtas Service ↩︎

- Remaining EED reporting deficiencies need immediate attention, Uptime Intelligence ↩︎